Thanks to my brother John Beal for finding this.

By Ted Johnson

From Variety

If you have problems seeing the video below click HERE.

youtube::XrtvUy47AVQ::

The last time “The Lone Ranger” appeared in theaters some 32 years ago, the hopes of the filmmakers were boosted at a test screening. As the unknown actor playing the title character bucked his horse and shouted “Hi-yo, Silver! Away!” and the William Tell Overture thundered on the soundtrack, the audience went absolutely crazy, recalls producer Walter Coblenz.

“The executive from Universal who was there said, ‘It is previewing better than ‘Jaws,’ ” Coblenz remembers.

As it turned out, that 1981 screening was the high point for “The Legend of the Lone Ranger,” which was both a notorious flop (the $18 million-budgeted film grossed just $12.6 million) and a public relations debacle before the movie even opened. Those who worked on the 1981 production chuckle at the mere mention of the film, made at a time when producers and studios were mining ’30s and ’40s serial characters for an emerging box office driven by blockbusters and merchandising opportunities.

“I can’t hide from it anymore,” quips Coblenz, whose credits otherwise include “All the President’s Men” and “The Candidate.”

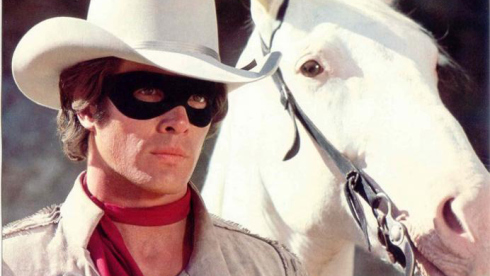

If the picture is remembered for anything, it is for the offscreen courtroom battle over who could wear the iconic mask, and the fate of the actor chosen to portray the new kemosabe (known as John Reid before he assumed his famous alter ego) — Klinton Spilsbury. It would be the 31-year-old actor’s first known credit. And his last.

Jack Wrather, an oil millionaire and TV mogul who controlled “The Lone Ranger” rights, was intent on bringing the story to the bigscreen. The success of the theatrical “Superman,” released in late 1978, only raised expectations that audiences would be interested in a character rooted in comics and serials of bygone generations.

Yet even as they set out to find the lead among unknown actors, just as Ilya and Alexander Salkind did with Christopher Reeve in “Superman,” the creatives faced a problem that the makers of “Man of Steel” did not: There already was a Lone Ranger, touring the country, making personal appearances and determined to continue in that role. Other actors had played the character, but Clayton Moore, who had portrayed him on television, was most associated with the masked man, which Armie Hammer will play in Disney’s July 3 bigscreen incarnation.

Wrather, who had let Moore appear with the mask for years, saw problems ahead if they began to market a new Lone Ranger with Moore, at age 64, traipsing around America as the character. But Moore was unwilling to surrender the role, and Wrather sued him, leading to a 1979 hearing in Los Angeles Superior Court in which a judge ordered the actor to remove the mask. It was a legal victory but a P.R. misfire.

Rather than sulk at his San Fernando Valley home, Moore continued to travel the country, still in character but wearing a pair of wraparound sunglasses instead of the mask. It was a publicity bonanza — he did more than 100 interviews that built sympathy for him, particularly among the children of the ’50s who had their own children, a potential audience for the movie.

“I intend to be the Lone Ranger for the rest of my life,” Moore told the New York Times.

Apparently set on the idea that he should star in the film, Moore rejected an idea of instead doing a cameo. But the producers also rejected an idea where he’d be the Lone Ranger, but hand off his mask to the next generation.

The controversy, however, did not keep the producers from assembling a topnotch team: William Fraker, the pic’s director, had helmed the classic Lee Marvin-Jack Palance starrer “Monte Walsh,” and was a famous cinematographer (though. Laszlo Kovacs was the d.p. for “Lone Ranger,” John Barry composed the score, and Jason Robards, Christopher Lloyd and Richard Farnsworth were cast in supporting roles. They didn’t skimp on production costs, with location shoots in Santa Fe, N.M. and even Monument Valley in Arizona. Spilsbury, chiseled and model-handsome, stood out in his screen tests, recounts Coblenz. and seemed to not only have the presence to carry the role but an all-American pedigree. He was the son of a legendary football coach at Northern Arizona U.

Michael Horse, an accomplished artist, was cast as Tonto, and brought with him a connection to “The Lone Ranger” of old: He was a friend of Jay Silverheels, who portrayed Tonto of the TV series. He even took acting classes from Silverheels. He initially had been reluctant to take the role, worried about stereotypes, but he talked to tribal elders and came to view it as a chance to “maybe do something” about Native American portrayals.

But neither Spilsbury nor the filmmakers knew what they were in for. Not only was there the comparison to Moore, still trekking across the country in character, but Spilsbury got into some scuffles off set that were reported in the press. Horse recalls one time when he got a call in the middle of one night, asking him to help out with Spilsbury, who had gotten into a fight. “I said, ‘This faithful companion stuff is only in the movie.’ ”

“Klinton was having his problems,” Coblenz recalls. “He was a pleasant enough person. I can’t say whether the whole idea of what he got into was more than he could handle. He was just having a very tough time.” I don’t think it was malicious. He was just frightened.”

By the time shooting ended, producers saw what they had was far short of the initial promise. “When you see the Lone Ranger, you have expectations of a strong voice, and it was never strong enough,” Coblenz recalls. So filmmakers enlisted another actor, James Keach, to dub Spilsbury’s voice. Yet that secret also leaked, to the point where Spilsbury, a bit miffed but still doing publicity, defended himself as he promoted the movie. “They wouldn’t have hired me if they hadn’t liked my voice,” he told the AP at the time. He told Interview magazine back then that the fights started in Santa Fe when “people would come up and start beating up on me. The cowboy-macho mentality is still really strong down there.”

Despite some promising screenings, and a gala premiere at the Kennedy Center in which President Reagan taped a message, the movie flopped. Coblenz knew it on Friday night of opening weekend. “The first weekend my wife and I were in New York, and I said, ‘Lets go to Times Square and see how long the line is.’ We were the line.”

Many of the cast and crew went on with their careers, but Spilsbury’s collapsed. Bo and John Derek wanted him for the lead in their Adam and Eve movie, but ran into opposition to the casting after “Lone Ranger” bombed, according to Variety. Spilsbury, who lives in Los Angeles and works as a photographer, didn’t return calls seeking comment.

Shortly before his death in 1984, Wrather released the mask to Moore to wear, which he continued to do until even he eventually gave up the character. Moore died in 1999.

The WB attempted a TV revival of “The Lone Ranger” in 2003, and by casting Chad Michael Murray as the lead, it seemed an effort to interest the “Dawson’s Creek” audience in the masked hero. But it, too, lacked the gravitas of the original, and the pilot was abandoned.

Coblenz, who also cites script problems with “The Legend of the Lone Ranger,” thinks that the newest attempt will work, based on the trailers he has seen.

“I think this new one is going to make it,” he says. “(It has) Gore Verbinski and Johnny Depp, plus an unbelievable amount of money.”

And at least this time there the “Ranger” really will be lone.