by Keith Ryan Cartwright

First appeared on the PBR website.

One of the PBR’s all-time greats talks about how the organization came to be.

PUEBLO, Colo. (July 1, 2011) – When Michael Gaffney walked into the Scottsdale, Ariz., motel room, he had virtually nothing.

He left having written a $1,000 check against the “hopes and dreams” of a better future, but by all accounts, he was broke.

“I needed this thing to work,” said Gaffney, of the mere idea of the PBR. He, like 19 other bull riders at the time, believed there had to be a better way of being rewarded for putting their lives on the line every time they nodded their head.

“When I went there, I basically had zero in the bank… and we were living on nothing – just scraping by,” Gaffney said. “It’s not like we went out and bought a bunch of vehicles or anything. The winnings just weren’t there.

“I had a stellar year in ’91, and I was basically dead, crack broke.”

Just four months earlier, Gaffney had ridden nine of 10 bulls at the National Finals Rodeo, but – as best he can recall – it had taken so much travel to qualify for the event that the roughly $50,000 he won during the season “was a wash, and I figured I was in the hole.”

It wasn’t until the NFR in December that he actually showed a profit for his efforts, and even then, Gaffney added, he needed those earnings to finance the travel costs associated with the early part of the 1992 season.

At the time, his wife Robyn was finishing up her undergraduate education and still had another four years of medical school at Texas Tech, followed by five more years of residency work at a local hospital in Lubbock, Texas.

“I won the average at the NFR and I finished in the Top 3 in the world, and I basically didn’t have [anything],” Gaffney said. “I can look back at 1991, and the only money I really won was at places like Del Rio and the Lazy E, when we were paying entry fees of $1,000.”

“I won the average at the NFR and I finished in the Top 3 in the world, and I basically didn’t have [anything],” Gaffney said. “I can look back at 1991, and the only money I really won was at places like Del Rio and the Lazy E, when we were paying entry fees of $1,000.”

According to Gaffney, even then bull riders were at the mercy of promoters.

Back then, Gaffney said it was common for riders to enter multiple PRCA events and then turn out of some after seeing the draw. He explained it was “cheaper to cut your losses” and pay an entry fee – along with an additional fee charged for requesting a specific day, as well as the turnout fine – then it was to pay for the travel after learning you had drawn a bull worth 58 to 65 points.

When the BRO came along, it paid more, but it too came with a price.

Shaw Sullivan, who Gaffney described as being a dictator, tried forcing the top riders to sign exclusivity rights, but veteran riders – the likes of which included Cody Lambert, Tuff Hedeman and Cody Custer – balked at the idea and walked out of a meeting in Denver.

Gaffney said Sullivan created a “ploy and scare tactics” to get young riders like himself, Aaron Semas and Wacey Cathey to sign the contract. Sullivan needed Lambert and Hedeman to draw a crowd, but excluded Custer from the BRO events because, according to Gaffney, “he didn’t like him.”

In what would become the first sign of solidarity between the top riders in the world, they finally banned together and told Sullivan that no one would compete unless he included Custer.

“Everything was a precursor to get to where we were in Scottsdale that particular day,” said Gaffney, who had been competing with a dislocated shoulder. “It was coming out at will, and I guess I was fortunate enough that it was my riding arm as opposed to my free arm.”

He would later discover that his other shoulder had been injured as well.

However, Gaffney labored through the competitions that year and tough times were made tougher.

In the early ‘90s, rider endorsements often resulted in product trade outs involving clothes and gear. There were a few riders, like Ty Murray and Hedeman, who had made names for themselves and with that, they were able to command endorsement money.

Gaffney remembers being approached once and making a product deal without the knowledge that David Fournier, another PBR founder, had been holding out for a small stipend.

“I cut him off at the knees,” said Gaffney, who had the same scenario happen to him a year later.

He added, “It was all an antagonist for the creation (of the PBR) to happen.”

The day he wrote a check to pay for his share of the PBR, he also paid a $400 entry fee at a rodeo, and despite riding four bulls, including one that had landed Lambert in an El Paso, Texas, hospital two weeks earlier, he said he only won $400 for his efforts.

Gaffney said that, like so many others, he was “on shaky ground” and thankful that the “PBR came to pass” when it did. Even then, the meeting was in April of 1992, and the first sanctioned PBR event didn’t take place until the fall of 1993, with the first season actually taking place in 1994.

He would eventually go on to win the 1997 PBR World Championship.

The year Gaffney won, there were only 18 events – compared to the 30 that make up a complete season in recent years.

During his title-winning season, which came six years before the organization began paying a $1 million bonus to the World Champion, he earned $243,251. He retired after the 2004 season, and a year later was inducted in the Ring of Honor.

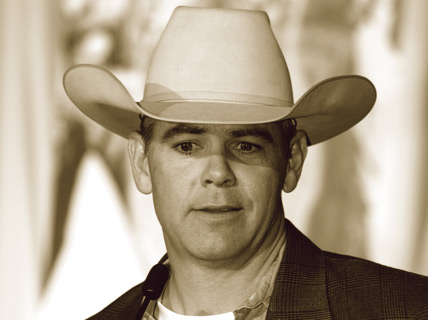

The 42-year-old New Mexican ranks as one of the PBR’s all-time greats.

“It was a big pipe dream like you wouldn’t believe,” Gaffney said, “a big hope that maybe we could change our destiny and change some of what we were having to go through – since we were the ones putting our lives on the line for little of nothing.”

In the coming weeks, other PBR founders and members of the Ring of Honor will share their stories of starting out and growing up in the PBR.

Heroes & Legends: Gaffney will join dozens, perhaps hundreds, of the biggest names in PBR history this October at the Legends Reunion at the Built Ford Tough World Finals.