by: Heather Smith Thomas

From Cattletoday.com

Most cattlemen raising horned breeds choose to dehorn their stock, since horns in the herd can be a nuisance and a hazard. The younger the better; dehorning a small calf is not as hard on the animal as waiting until the horns are well grown, with a large blood supply. But sometimes the stockman has no choice, as when purchasing yearlings or older animals that still have their horns. Care must be taken to avoid serious blood loss when large horns are removed. But an animal can be dehorned at any stage of its life if removal is done properly.

Dehorning young calves is easiest, for the horn buds are small. Some stockmen dehorn at birth, using a caustic paste that kills the horn buds, applying it when the calf is a few hours or just a day or two old. This usually works if the paste is applied properly. Some cows will lick it off their calves, however, and cow and calf may have to be separated temporarily to avoid having the cow lick off the paste before it has done its work. Also care must be taken to protect the calf from wet weather that might cause the paste to run down the face.

A lot of calves are routinely dehorned during the first few months of age, at the time of their spring vaccinations. At that age, the horn buds can be scooped out with a special tool, or seared with a hot iron to kill the horn producing cells. Electric dehorners are often used for this, for they create a high, even heat. If using an electric dehorner, choose one of proper size for the calves. A dehorner too small may not be adequate for larger horns and won’t kill all the horn cells resulting in horns on some of the calves, or deformed horn stubs. A dehorner too large is difficult to use on small horn buttons, and you either do a poor job of dehorning or end up burning a lot more tissue than necessary, making the calf’s head sore longer and slow to heal.

When using any electric dehorner, make sure it is working properly and heating fully and consistently. If it fails to get back up to full heat between calves, or has some other problem, you may end up with some horns or horn stubs. Horn cells that are damaged but not killed can produce unsightly, abnormal horns (short, heavy, thick stubs, or horns that grow crookedly and perhaps curve around into the animal’s head as they grow). Make sure you apply enough heat long enough to completely kill the horn bud. The outer shell should come off, and heat should be applied again to the underneath tissue and its surroundings.

Dehorning calves with a hot iron (such as an electric dehorner) is bloodless and you have no risk of excessive bleeding. But the burned area will be sore and painful for a few days. You can minimize the extent of the burn, however, if you clip the area first. We use electric clippers to get rid of extra hair around the horn buttons. Then there is less burning hair and damaged tissue around the horns, which is often what hurts the calf the most and takes so long to heal. Any time there is burning hair, the area becomes much hotter, with a deeper and more painful burn over a larger area.

On large calves or weanlings, the horns are usually too big to kill by burning and searing, and some type of horn clipper or nipper is generally used to cut off the horn at a fairly deep level (to get the horn growing tissue at the base, so the horns won’t regrow). If the horns are good size, the arteries supplying them with blood are also fairly large, and there may be quite a bit of bleeding. Some stockmen use blood stopping medications to help coagulate the blood and get it to clot and slow; others use tweezers to “pull” the bleeding vessels and clamp and crush them. A torn or crushed vessel always stops bleeding quicker than a clean cut one; the edges draw together better and blood clotting is swifter.

A dehorned animal with fairly good sized horns will always spurt blood for a few minutes, but normal blood clotting action will generally slow and stop the bleeding before the animal loses too much blood, unless there is some unusual circumstance such as lack of blood clotting ability (which can happen if the animal has been eating sweet clover or some other plants that contain chemicals that interfere with proper blood clotting), or strenuous exertion and/or excitement following dehorning which keeps blood pressure elevated and the bleeding going longer. Dehorned animals should be stressed as little as possible before, during, and following the procedure.

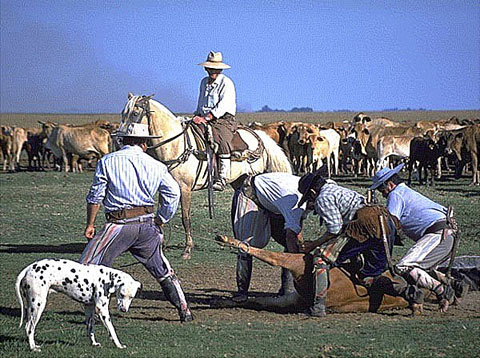

If dehorning yearlings or older animals, you’ll need to remove the horns with a horn saw, since they are generally too large to remove with nippers. A horn saw can be used best if the animal is restrained in a chute, with halter and/or nose lead secured so the animal can’t move its head around while you are sawing. It’s often easiest to pull the head around one way to do the first horn, then the other way to do the other side.

Over the past 25 years my husband and I have dehorned a number of mature animals with very good success, leaving about one eighth inch of horn on the bottom side to give a small “lip” for anchoring a temporary tourniquet to halt bleeding. A mature animal can bleed profusely when dehorned, squirting blood for quite awhile. But you can stop the bleeding quickly and completely by tying baling twine around the poll, tight under the horns. The large arteries that supply the horns are not far under the surface of the skin at that spot under the horns, and by putting pressure on them, you can stop the bleeding.

To get the tourniquet tight enough, we tie one string around the poll, anchored under each horn, then pull it even tighter by tying another string over the top of the head, pulling up on the first string, front and back. This pulls it very tight under the horn on each side and shuts off those arteries. We leave the twines on for a day or two, then put the animal back into the chute and cut off the twines. By then the area has started to heal and there will be no more bleeding.

Apply the tourniquet right after you saw the horns off. It doesn’t work as well to try to tie it on before the sawing; you invariable disrupt the twines during the dehorning process. Leaving a small amount of horn (enough to secure a twine tourniquet) may mean that the horn may grow a little perhaps becoming an inch long stub over the life of the animal — but it enables you to be sure there will be no serious blood loss or risk of losing the animal, and it also means less exposed horn sinus. When you saw off a large horn right down as close as possible, you expose more of the cavity into the horn sinuses, which can be vulnerable to infection.

Infection in a horn sinus can be hard to clear up; sometimes the outer surface heals over and the infection has to break out again weeks or even months later. A healed horn may suddenly start draining pus, or thick, clear jelly like material. Sometimes the first sign of trouble will be the animal going off feed, dull and acting as if the head hurts. These cases will generally need antibiotics.

We’ve never had problems with the horns we’ve sawed off leaving room for a tourniquet. For instance in 1969 we bought 18 purebred Hereford cows and dehorned them all, along with one mature bull who was very wicked with his horns, and had no after effects. Using the twine tourniquet method, we had no bleeding, and no infections. In the years since then we’ve dehorned a number of other cattle this way, including some yearling bulls, and feel it is the safest and most trouble free method for removing large horns.

If you are planning to dehorn mature animals, do it before or after the fly season, or you may have problems with maggots in the horn cavities (until they heal and fill in). If flies lay their eggs in the holes, you’ll have to use a fly killer repellent (such as KRS) to get rid of them. Also, avoid dehorning during or just prior to severely cold weather. An animal can “catch cold” in those exposed horn sinuses and give you problems also. But with proper precautions and care, you can successfully dehorn cattle at any age.