Today’s guest blog is by Heather Smith Thomas.

Today’s guest blog is by Heather Smith Thomas.

Heather is a really interesting woman who writes articles for many horse and livestock publications. You can learn more about her at the end of this article and I encourage you to do so.

This article originally appeared in New Mexico Stockman magazine.

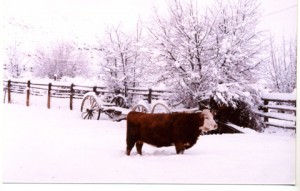

Weather is always a factor in cattle health.

Stressed animals are always more vulnerable to stress-related illnesses. Cattle need more care during cold or wet weather. Management to prepare cattle for winter and minimize these stresses can save or make you money, and reduce the incidence of illness or loss.

As days get shorter and weather is colder, body metabolism increases. Feed intake increases and passage of feed through the digestive tract speeds up. Feed requirements for cattle may go up as much as 10 to 15 percent. All of these changes contribute to an increase in heat production so the animal can withstand winter temperatures.

Body condition is extremely important during winter. Cows that get too thin during a cold or wet winter suffer more cold stress than fatter cows (since fat serves as insulation and a source of energy reserves). A thin cow must rob even more body fat in order to keep warm. It becomes a vicious cycle.

Calves born to thin cows may be compromised in body condition and immune health, and more prone to disease during their first weeks of life. Calves from thin cows may be born weak, unable to get up quickly and nurse—not getting colostrum soon enough. Cold stress also hinders a calf’s ability to absorb colostral antibodies. Thin cows may not produce adequate levels of antibodies in their colostrum if they have been short on protein in their diet. Calf survivability is always lowered in thin cows, as is the cow’s ability to rebreed.

Windbreaks and bedding should be provided during winter storms if you live in a cold climate, so cattle won’t expend so much energy just to keep warm. Without bedding, energy requirements in sub-zero weather may increase by 12 to 15 percent on a cold night, just to offset the heat lost when cattle have to lie on cold ground.

If weather is cold and windy, cows must eat more food to keep warm. If they stand behind windbreaks or huddle in a group to protect themselves from the wind, rather than grazing, they can’t eat enough to maintain body heat. Even if pasture is available, they may not start grazing until temperatures are warmest in midday, and they lose weight because they’re not eating enough total feed. Under these conditions you need to feed hay or a supplement early in the day to get them going, and then they’ll usually start grazing.

Short days and long nights are part of the challenge in getting cattle to eat enough. Grazing time is shorter, so extra feed may be needed, to make sure the cattle eat enough to keep warm and to maintain body condition. They will often eat hay during the night but they generally won’t graze at night during cold weather.

Cattle need to eat more roughage (forage) to provide the calories for heat energy. If they don’t eat enough fibrous feed (which is broken down in the rumen to produce energy, with the fermentation process creating extra heat, as well), pounds melt off as they rob body fat to create the energy needed for warmth. With more total pounds of roughage in the diet, either as pasture or some additional grass hay or good quality straw, the cow can keep warm—as long as she has enough protein to feed the rumen microbes that ferment and digest the roughage.

In cold weather, high quality leafy alfalfa by itself is not the best feed. Even though it supplies plenty of protein, calcium, vitamin A and other important nutrients, it does not contain enough fiber to provide heat energy during cold weather. Cattle being fed high quality hay as their only forage source will lose weight in winter. Alfalfa alone is not adequate for cattle when weather is really cold; they gobble it up and stand around shivering. They must have more fiber in the rumen to create heat energy.

If a cow is cold, she needs all the roughage she will clean up. You don’t dare feed that much high quality alfalfa or the cow may bloat. Alfalfa for beef cows should be lower quality (containing more stems/fiber and less leaves) or a grass/alfalfa mix if it’s being fed as the primary forage source, or should be fed in very small quantities as a protein supplement. A small amount of good alfalfa per cow per day can augment the protein and mineral/vitamin levels of poor quality roughage such as dry pasture or low quality grass hay or even straw, balancing the diet and enabling the cow to utilize the poorer quality forage to best advantage. When it gets really cold, cows can do fine if you feed them all the poor quality roughage they can eat—whether straw or low quality, mature grass hay—and enough alfalfa to provide the necessary protein for digesting it.

ADUSTING GRADUALLY TO COLD WEATHER

ADUSTING GRADUALLY TO COLD WEATHER

Cattle that have a chance to acclimate gradually to winter develop a thick hair coat and put on body fat if feed sources are adequate. Hair and fat both serve as good insulation against the cold. If you have cold winters, select a type of cattle with a naturally thick hair coat, that fatten easily. They’ll handle the cold much better than the breeds that were developed for hot climates.

If you live in a cold climate and buy cattle from a warmer area, bring them home before cold weather starts, so they will have time to grow a good hair coat. With short summer hair, the typical beef cow may chill when temperatures drop below 40 degrees F. whereas a cow with a heavy winter coat can stay comfortable at temperatures below zero F. if there’s no wind. She can also adjust to cold weather by increasing her metabolic rate, to increase heat production. Increased metabolism will also increase her appetite and she’ll eat more, to help her keep warm.

But if a cow gets too cold, heat loss and cold stress will reduce her appetite and decrease her efficiency of feed conversion. Body metabolism is adversely affected if body temperature drops. Mammals must maintain a fairly constant body temperature to keep up the metabolic processes that enable the body to function.

If temperatures drop below the animal’s comfort zone, there’s not only an increase in maintenance requirements, but digestibility is also reduced. This further increases the feed needs of cattle. Research has shown that there’s a decline of about 1 percent in feed digestibility for each 2 degrees of temperature drop. But cattle that are adapted to cold weather have more efficient digestion at cold temperatures than unadapted cattle and are more resistant to the depressing effects of cold on digestion.

If a cow has a good winter coat, she does fine until temperature drops below 20 to 30 degrees F. Below that, she must compensate for heat loss by increasing her energy intake, to increase heat production and maintain her body temperature. Healthy cows in average body condition (body score 5) or higher, acclimated to cold weather, have a “lower critical temperature point” of about 20 degrees F. This is the point at which maintenance requirements increase and you must feed them more. This is the lower limit of the comfort zone, below which the animal must increase the rate of heat production. This is also the temperature below which an animal’s rate of performance (growth, milk production, etc.) begins to decline.

A 1100 pound pregnant cow needs about 11.2 pounds of total digestible nutrients (TDN) per day when temperatures are above freezing or even above her lower critical temperature point which may be slightly colder than freezing. If the temperature drops 20 degrees below her lower critical temperature, she needs 20 percent more TDN (2.2 more pounds of digestible nutrients). To supply that, you can feed her 5 pounds of hay containing 50 percent TDN. Your county agent or a cattle nutritionist can help you figure out the nutrient quality of your hay.

Wind or moisture will make the effective temperature (felt by the body) lower than the temperature stated on a thermometer. Always figure in the wind chill (using a standard wind chill chart) when arriving at the number of degrees below a cow’s critical temperature point. For example, a 10 mile per hour wind at 20 degrees F. has the same effect on the body as a temperature of 9 degrees with no wind. A 30 mile per hour wind at 20 degrees would be very similar to zero degrees on a calm day. If temperature drops to zero, or the equivalent of zero when figuring in the wind chill, the energy requirement of a cow increases something between 20 and 30 percent, about 1 percent for every degree of coldness below the cow’s critical temperature.

Cattle can’t eat enough extra feed to compensate for heat loss at minus 50 degrees (which would be the case at 15 below zero with a 40 mph wind, for instance). In these conditions, they need windbreaks to reduce heat loss during winter storms. During severely cold weather, cattle also need bedding to insulate them from frozen ground, which will also help conserve their body heat.

Cattle of British breeds and crosses, with normal winter hair coats, need about 1/3 more feed than normal when exposed to a wind chill that brings effective temperature down to zero. Critical temperature for any individual animal, however, will vary according to age, size, hair coat, moisture conditions, fat covering, length of time exposed to adverse weather, and wind speed. Feedlot steers, for example, with extra fat and access to windbreaks, are usually less stressed by cold weather than are cows grazing out in the open.

Cold stress is also less severe if a storm is brief, compared with continuous bad weather. Temperatures, wind chill charts, and any measures of cold stress are always based on 24-hour averages. If cattle have windbreak protection so they can periodically seek shelter and get out of the wind when weather is really bad or when they are resting after eating, their exposure to cold stress is intermittent rather than continuous, and the severity of wind chill is reduced.

WET WEATHER

Lower critical temperature changes when cattle get wet. Even though a cow with a good hair coat may be comfortable when temperature gets down to freezing, or even down to 20 degrees F, if she gets wet from rain or continuous snow her comfort zone is narrower; she may chill if the temperature is below 50 to 60 degrees. A thin cow with a poor hair coat, or any cow that gets thoroughly wet, needs more feed in these conditions. A cow that’s wet will need 40 percent more TDN at 30 degrees than the same cow with a dry hair coat.

With severe wind chill and wet conditions, it is impractical or impossible to feed enough additional energy to provide the calories needed—especially if you try to use grain as the supplemental energy source, since that much grain would cause digestive disorders in cattle that are not accustomed to eating grain. It’s much more cost effective to provide windbreaks to offset wind chill, and to have cattle in adequate body condition for winter—with enough energy stored as fat, for reserves.

A wet storm is always harder on cattle than dry cold. Wet hair can’t keep out the cold and the cow will chill. If hair is dry, it stays fluffy and traps body heat in tiny air spaces between the hairs, creating a blanket of insulation between the cow’s body and the cold air. Hair will shed water for a while; the water will run off because of the natural oils that make the hair coat somewhat waterproof. But once it gets completely wet—as in an all-day rain or severe snowstorm, the hair lies flatter and its insulating quality is lost. Cattle suffer a lot more cold stress in wet weather than in dry cold. They can be fairly comfortable at 10 below zero F. on a still, dry day, and quite miserable at 35 degrees in a storm with rain and wind.

All too often stockmen tend to overlook the effects of wet weather, because the temperature isn’t really cold. Yet a cow’s nutrient requirements may be greatly increased, because she has more trouble keeping warm. Try soaking your shirt in water and see how poorly it insulates you from wind or cold. Cattle that have lost weight or are losing weight are very susceptible to cold or wet weather stress, and more apt to become sick, so keep track of body condition during fall and winter.

Cold, dry weather tends to stimulate appetite, but rain or snow may create temporary reduction of feed intake by as much as 30 to 100 percent, so make sure cattle have plenty of feed after the storm is over, to make up for the deficit.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Heather is a really interesting woman who writes articles for many horse and livestock publications and has written 20 books, most of them about horse and cattle care management. You can see some of her work at Storey Publishing by clicking HERE.

One of her other publishers, Oak Tree Press, published her book Beyond the Flames; A Family Touched by Fire which she wrote after her daughter’s severe burn injuries 11 years ago, and how it affected their family and totally changed their lives. You can order the book by clicking HERE.

She also has an interesting blog, telling about her family and her experiences, including her ranching lifestyle and what’s been happening since that incident. That blog is HERE and I look forward to her entries.