From the The Cattleman Magazine

Texas and Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association

By Lorie Woodward Cantu

Ranching is a business of change, generally driven by the volatile forces of markets and weather. Successful ranchers seek out management strategies that are flexible enough to allow a quick, appropriate response to forces that are beyond their control. Planned grazing maximizes flexibility.

“In today’s world, you have to have flexibility on the livestock and grass sides of the equation to survive,” says Gary Price, who operates the 77 Ranch in the Blackland Prairie of Ellis and Navarro counties.”With planned grazing you set goals, monitor your progress toward those goals, and constantly evaluate what you’re doing, so you’re in a position to respond to changes quickly, maximizing opportunities and limiting possible damage.”

Price began implementing planned grazing more than 30 years ago when he noticed how grasses such as big bluestem, which were remnants from the native prairie, responded to good grazing management that included moderate use and adequate recovery during the growing season.

“At the turn of the 20th century, Ellis County had produced more cotton than any other county in the nation,” Price says. “Those big farming families were good at hoeing grass out of their cotton fields, so we were fortunate to have remnant stands of native grasses on the slopes in our pastures. Essentially, I saw the potential of those grasses and then I dedicated myself to learning how to unlock their potential.”

Keys to decisions

The decision-making processes within planned grazing gave him the keys he was looking for.

One key was focusing on the power of water and vowing to capture every single drop that fell on his land, he says. Why? Obviously, grass — regardless of the species — doesn’t grow without water. The ranch is located in a 35-inch rain belt, but is subject to drought just like drier regions. During a particularly devastating drought in 2005 and 2006, Price noted that 30 stock tanks and a 10-acre lake that had been built in the 1950s dried up.

To increase water infiltration, organic matter is essential. Because much of the land had been farmed intensively, organic matter was rare.

“You can’t control how much rain you get, but you can control how much you keep. Because we were trying to rebuild organic matter, we had to come to the realization that weeds were better than no cover at all. You have to start somewhere, and then you manage your grazing, so that your plant communities change for the better over time,” Price says. He uses all the tools at his disposal including herbicide and re-seeding when appropriate.

The 2,000-acre ranch is divided by a farm-to-market road, so historically Price has run 2 herds in separate rotations. Over the years, Price has acquired additional adjoining land, in tracts ranging from 30 acres to 150 acres. To minimize costs, he used the existing fences and made only the modifications necessary to enhance cattle movement.

He has owned some property for as few as 5 years. Each side of the ranch has 15 paddocks of various sizes displaying a wide range of forage quality, creating what Price described as a “mottled pasture situation.”

“Managing our grazing has inherent challenges because we have land that has been influenced by some of the very best management, and land that has been shaped by some of the very worst,” he says. “At any given time in our rotation, we may be moving a herd from the best pasture to the worst, or vice versa. The original footprint will always be on the land, so we’ve learned to work with the differences, always striving to make things better.” Under average conditions, the pastures get a 7- to 8-week rest between grazings.

Forward momentum

Price considers each paddock a separate entity and sets goals for each, constantly monitoring conditions as he rotates his cattle through. For instance, in paddocks that have been re-seeded, Price is acutely aware that the Blackland gets friable as it dries out and 6-inch seedlings can be pulled up by the roots. In this situation, he might hold the cattle in a more established pasture for longer than he prefers to help protect the seedlings and the more vulnerable plants.

“You’re going to make mistakes as you go along,” Price says. “Sometimes I am forced to take actions that I consider mistakes, such as leaving cattle in a pasture a little too long to protect something else, but I always know why I did what I did and what I will need to do to make up for it in the future. Planned grazing gives me the flexibility to do whatever I need to do without losing the overall forward momentum.”

Because flexibility is integral to planned grazing, it allowed Price to change his mindset about “standard operating procedures,” such as hay production, which is a long-standing tradition in Central Texas.

“I have changed my mindset from growing hay to growing grass,” Price says. “I knew there had to be a better way because hay has so much labor built in and cows can’t eat labor.” Under normal circumstances, Price matches the number of animals he’s carrying through the winter to the available forage, and supplements the standing grass with cottonseed cake. With that, he says he has kept a 100-acre coastal Bermuda bottom that a neighbor hays on percentages. Price holds his portion as a reserve for winters like this past year that were particularly cold, wet and hard on livestock.

At the moment, Price is changing the ranch’s cow herd to better meet the demand of the niche market for all-natural beef. Traditionally, the ranch was home to F-1 Braford cows that were bred to Charolais bulls. Now, Price is switching to Super Baldy (one-half Angus x one-quarter Hereford x one-quarter Brahman) cows bred to Angus bulls. He will continue to wean and precondition the calves, which are contracted to a natural beef provider through private treaty sales. Although the weaning weights are expected to decrease slightly, Price believes that the difference will be made up through value-added practices, such as source- and age-verification and preconditioning the cattle to the buyer’s specifications.

The transition has necessitated buying and calving out a higher than normal number of heifers, which has affected the rotation schedule, but has not derailed the progress.

“This transition, which was prompted by marketing needs, has required us to be flexible, and we’ve been able to respond,” Price says. “I’ve always focused on optimum production, not maximum production that has to be propped up with inputs. Of course, planned grazing is not a quick fix, but it put us on the right path for steady progress and sustainability.”

Rewards for good stewardship

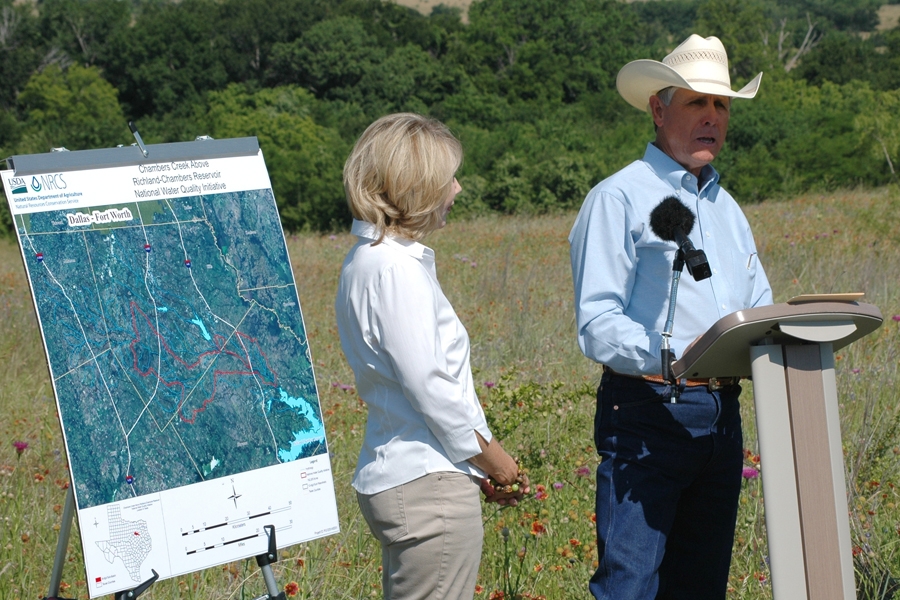

The progress Price has made in improving the land has not gone unnoticed. In 2007, Price received the Leopold Conservation Award for Texas, the highest land stewardship honor bestowed by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department and the Sand County Foundation.

Knowing that it is possible to successfully manage for both livestock and wildlife while improving the range, Price regularly hosts field days and tours on the ranch, demonstrating how he has renewed and restored the native Blackland Prairie in his care. In recent years, he has noticed an increasing number of ranchers who are interested in native grasses and management that allows them to enhance their land and their bottom lines.

“When I first implemented planned grazing, I was accused of ‘wasting grass,'” Price says. “Now people can see that standing grass is not wasted, its benefit is just being consciously deferred. There’s more interest now in native grasses than I’ve ever seen in my lifetime. People are searching for production practices that are practical and sustainable.”