From the Denver Westword website

“The West is not a place,” Jack A. Weil would say. “It’s a state of mind.”

Jack A. entered that state for good in 1928, when the then-27-year-old salesman for Paris Garters drove his brand-new Chrysler Roadster across the plains to Denver. Born in Evansville, Indiana, the son of a Jewish refugee who’d come to this country alone when he was just sixteen, Jack A. had been given the chance to trade his Memphis-based territory for a new office in Denver, covering everything from El Paso to the Canadian border, and he and his new wife, Beatrice, were up for the adventure. “We fell in love with this country,” Jack A. told me a few years back. “To see all the wide-open space, to see the future, I knew I was home.”

He saw a future, his future, in the West, a land of endless opportunity. A place where you could make something not only of yourself, but make something that mattered. You just had to believe — and then work very hard.

The couple scrimped and saved for a decade until they finally had enough money to buy a house. By now, Jack A. was tired of all the travel — he had a son, Jack B., and a daughter — and he’d taken a job with the Stockman Farmer Supply Company, convincing owner Phil Miller to get rid of the “Farmer” and focus on Western attire that would appeal to people other than cowboys. After all, Jack A. explained, “If they had any sense, they wouldn’t have been cowboys. But I thought there was a tremendous future in promoting this thing. I didn’t know anything about the business, but I knew what I wanted. In my love for the country and its potential, I figured we had a product. I knew how I felt about it. I knew about the romance of the country.”

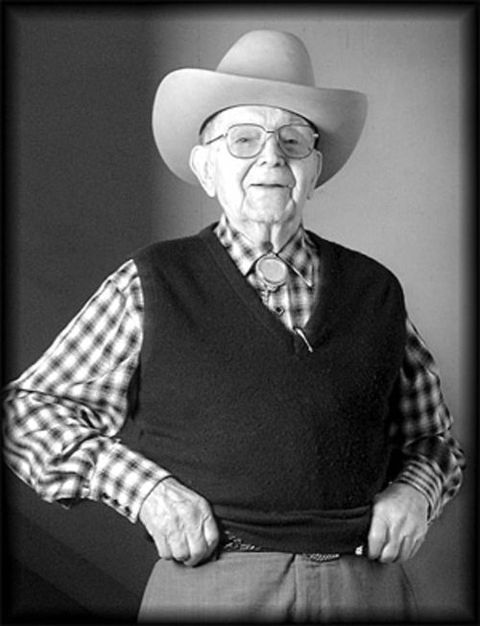

In 1946, Jack A. founded his own company, Rockmount Ranch Wear, devoting himself full-time to that romance. (His wife, who passed away in 1990, always referred to the business as his “mistress”; Jack A. referred to Beatrice as “the Boss.”) And he set out to show everyone how the West was worn. He popularized the bolo tie — his favorite clasp was an American silver dollar from 1901, the year of his birth — and created sawtooth pockets for his shirts, which he fastened with distinctive, diamond-shaped snap buttons now that the end of World War II had eased the metal shortage.

Jack A. Weil wasn’t the first person to strike out for a frontier and make a life and fortune there, and he won’t be the last. But he did it with style and substance and grit, in the process helping to define Denver, this center of the new West. And all that time, he just thought he was working. It wasn’t until around his hundredth birthday that the city really took notice of Jack A. and started renaming a stretch of Wazee Street after him every March. The 1600 block of Wazee had changed a lot since the days when the five-story warehouse was surrounded by other wholesale operations and businesses; it was now lined with lofts and galleries and restaurants that pointed the way to Coors Field. Steve Weil, who’d joined the family business more than a decade before, persuaded his father, Jack B., and his grandfather that Rockmount should add a retail shop, and even spruce up the old space.

The result is a combination museum/Western-wear store, a must-stop for anyone visiting Denver, the most seductive tourist trap ever devised, filled with stylish boots and belts and those Rockmount shirts, the ones seen on rock stars and in Brokeback Mountain.

And on so many of the people who came to Jack A. Weil’s memorial service this past Sunday.

It was not just a well-dressed memorial service, but a real celebration. Before he passed away on August 13, Jack had lived more than 107 years, and he’d lived those years well, filling them with great stories and sayings that spilled from his grandchildren as they shared their memories. “Was ain’t is,” a granddaughter remembered him saying, to show how life kept moving, kept changing. But one thing didn’t change: You worked. And so even as the city made “Papa Jack” a marketing icon, even as the “country’s oldest CEO” accolades started coming in, he just kept working. Jack A. would get up every morning, Steve remembered, read the obituaries, see that he wasn’t in them, and go to the office.

He kept working even after Jack B. passed away, greeting visitors to the store and telling his stories, showing the “government surplus” mule that had two rear ends and no head, pointing to the signed picture of President Ronald Reagan. “When he was elected, he started talking about a ‘service economy,'” Jack A. remembered. “I wrote back that when I was growing up in Evansville, only a hundred miles from where he grew up in Dixon, ‘service’ was what happened when we took a mare to stud.”

Jack A. was a Republican — “a guy should only be a Democrat until he makes a little money,” he’d say — but he was also a true son of the West, even if he was born in Indiana, and arrived here in a new Chrysler rather than on a horse. “Styled in the West by Westerners since 1946,” proclaims the Rockmount slogan — and really, what matters is not where you came from, but what you do here.

Was ain’t is, and no one would have gotten a bigger kick out of all the people who will be in Denver for the Democratic National Convention than Jack A. Weil. He would have greeted customers and told his stories and helped set the stage for the future, for a time when all things are possible. When a 107-year-old CEO can become a city’s poster boy, and Barack Obama can stand in that city’s football stadium to be nominated as the Democratic candidate for President of the United States.

The West is not a place, but a state of mind. And this week, it’s wide open.