By Andrew Schneider

From the NPR blog The Salt

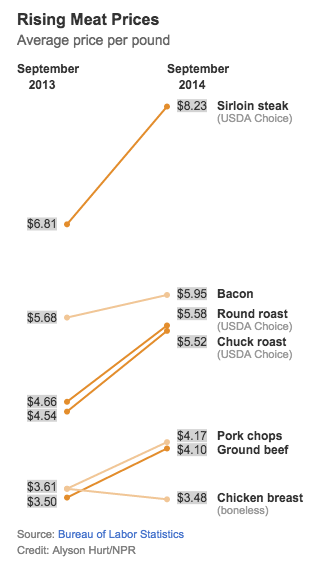

If you’ve shopped for meat recently, you no doubt have noticed that beef prices are up. Some grades are even at the highest levels ever recorded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Though the inflated prices may be hard on consumers, they’re helping Texas cattle ranchers recover from a fierce drought.

On a sprawling ranch called 44 Farms in Cameron, Texas, about two hours’ drive northwest of Houston, cattlemen raise Black Angus, the most common breed of beef cattle in the U.S. The ranch recently held its fall auction, but none of the animals were headed for the dinner table anytime soon. Instead, they will be giving birth to a new generation of cattle.

Until recently, most Texas ranchers were reducing the size of their herds as they struggled with years of drought. A relentless sun withered the grasses and grains that cattle eat. During the worst of it, feed costs soared for ranchers.

“Our grasses were dying just from the lack of moisture. We were feeding just corn stalks and anything else we could find to maintain the cattle through that tough time,” McClaren says.

Finally, ranchers had to respond by reducing herds to cut costs.

Finally, ranchers had to respond by reducing herds to cut costs.

“The drought was so severe for so long, and the feed prices were so high, that you just couldn’t do that forever,” says David Anderson, a livestock economist with the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service. “We do have producers who were forced to sell off all their herds. A lot of those beef cows did go to slaughter.”

Meat is displayed in a case at a grocery store in Miami in July. Pork and beef prices are up more than 11 percent since last summer.

Meanwhile, the U.S. economy has been improving, so more Americans want to grill beef again. Now the demand for beef is rising, just as packing plants are running out of excess supplies. The result is predictable: Beef and cattle prices are going through the roof.

Consumers may hate it, but those higher prices are making it possible for ranchers to purchase expensive feed in those areas — like the Texas Panhandle and north-central Plains — where land remains badly parched. In other parts of Texas, the drought has eased, allowing ranchers to start rebuilding herds. That means McClaren is seeing strong demand for his cattle.

“We have had calf prices at auction pushing $3 a pound,” Anderson says. “That is twice as much as what we would have thought in the past being tremendously high prices.”

The fall auction at 44 Farms drew hundreds of bidders. The ranch made roughly $3 million in just a few hours, more than double the take from last year’s fall sale. McClaren is already gearing up for his next auction in February.